This summer saw the release of a study commissioned by 11 European gas transmission system owners/operators (TSOs) analysing the possibility of a European hydrogen network1. This imagines a project which will see the creation of 23,000km of hydrogen-capable pipelines by 2040.

The catalyst for such an ambitious undertaking is two-fold: the European Green Deal (EGD) and falling demand for natural gas. The EGD aims to transform the 27-country bloc to a low-carbon economy, and as part of this it sets out the EU’s new support mechanisms for green hydrogen. This includes setting goals for the introduction of electrolysis capacity and utilising green hydrogen across industrial sectors. Additionally, low carbon “blue” hydrogen will also have a role to play in the short to medium term.

In most accelerated climate scenarios, aggregated natural gas demand in the EU is expected to decline over the next decade, in part due to the electrification of heat in buildings and through substitution by green gases. By 2040 that demand is predicted to be approximately 50% of current levels.

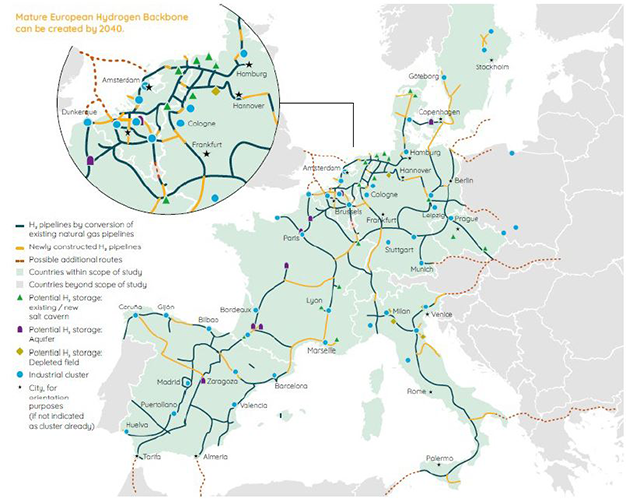

This shift doesn’t necessarily mean, however, that existing gas network owners/operators will be cut loose with their stranded assets. If anything their role – and their hardware – will be given more clarification in the energy transition: transmission pipelines for hydrogen do not differ significantly from natural gas, and with a little modification around optimising pipeline dimensions relative to compressor station capacity can be retrofitted to transport 100% hydrogen. The cost of this is estimated at 10%-35% of that of building new pipelines. These existing pipes will account for 75% of the proposed network. The remaining 25% will be new pipelines. This will create a network of pipeline running across Germany, France, Italy, Spain, the Netherlands, Belgium, Czech Republic, Denmark, Sweden and Switzerland (Figure 1).

The study estimates the cost of the project to be €27-€64 billion. This quite wide-ranging figure is based on a number of assumptions for energy prices, pipeline and compressor station costs, and is stated to be “relatively limited” in the overall context of the transition, and substantially lower than some early estimates. The study also believes that it is feasible to operate hydrogen pipelines at less than maximum capacity, leading to substantial savings on investment in compressors, operational costs and energy consumption. The network is also deemed cheaper than transportation by ship.

The development will occur over three phases: an initial 6,800km pipeline network by 2030, connecting hydrogen valleys, with planning starting in the early 2020s; and a second and third phase which will see the infrastructure expand further by 2035, and then stretch in all directions by 2040 by up to 23,000km. By this time the proposed backbone could adequately meet 1,130 TWh of annual hydrogen demand in Europe. The study states that this could be based on solar PV in Spain and Italy, or offshore wind on the north and Baltic seas, and that blue hydrogen – whereby the carbon emissions are captured and stored, or reused – could also be produced at industrial clusters with good transport links to carbon storage locations. Further network development would also be expected up to 2050.

Distribution network operators (DNOs) might also have a key role to play in the future in delivering hydrogen to industrial users. However, the impact on them of the expected falling domestic demand over the next 20-30 years will require close monitoring on a region-by-region basis. There are also some known unknows around the project in the form of future supply and demand dynamics of an integrated energy system that includes natural gas, hydrogen, electricity and heat.

The key concerns for existing bondholders of TSOs, of course, would be the certainty of recovery of long-term capital expenditure and agreeing allowed returns on future investments with national energy regulators. Early initiatives from TSOs based on the EU’s wider stance on achieving a low-carbon economy should enhance the prospects of long-term regulatory support. This is positive for bondholders. The attraction of bonds issued by regulated utilities is the predictability of earnings and thus preservation of strong investment grade ratings. These features epitomise defensive characteristics favoured by our IG funds.