Failure to address disparity between genders could lead to various forms of societal and economic losses. We’ve been engaging with 26 of Asia’s most influential companies on this topic.

Gender and the risk to GDP

Gender disparity is a chronic problem in many Asian countries and a failure to address this issue could directly and indirectly lead to various forms of societal and economic losses. Not doing so means that half the population risks being systematically marginalised and excluded in the workplace. We discuss the socio-economic issues prevalent in these markets and explain how we have been engaging with companies at the board level. Our ambition is to make companies aware of related issues and help them understand how to improve gender inequality and reduce potential negative impacts on their businesses and the wider economy.

Societal and economic losses

Demographic and economic crisis – a country needs a birth rate of at least 2.1 to ensure productivity and the stability of the population. Yet, that’s not the case for many developed countries particularly in Asia. According to the CIA’s The World FactBook (February 2024), four Asian countries/regions had the lowest estimated fertility rate globally in 2023: Hong Kong (1.23), Singapore (1.17), South Korea (1.11) and Taiwan (1.09). Low fertility rates in conjunction with an aging population create the risk of even greater long-term societal harm. Declines in production and innovation, stagnating economic growth together with increases in health expenditure and a pension crisis, are issues that we are seeing rear their head in Japan.

The causes of gender disparity

Culture norms – the traditional Confucian system influenced the formation of contemporary societies in the region, and against this backdrop, women are still expected to the be main caretakers for the family. While both men and women face mounting pressure from the cost of housing, elderly care and children’s education, women still predominantly bear the responsibility for household maintenance and caregiving in many advanced Asian economies. With limited infrastructure support, women tend to face greater pressure to give up their careers after having children. This has devastating impacts on workforce diversity and productivity.

Political direction – Political leanings and government policy contribute to different forms of gender disparity in each market. For example, South Korea is currently dealing with one of the lowest female employment rates and birth rates globally, with the capital Seoul having recorded a 0.593 birth rate in 2022. Gender themes became a pivotal point in the presidential election in 2022. President Yoon’s policy to abolish the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family raised concerns of further exacerbating the issue.

At the same time China is still battling with the long-term effect of the “one-child policy”. The preferred male offspring bias had considerable impact on family structure and has reinforced societal gender stereotypes. The resulting severe gender imbalance led to further social problems such as human trafficking and other forms of gender-based violence.

Lack of a support for women – at work or at home – The prevalent long working hours and overtime “culture” made it very difficult for dual-income families to raise children. Employees are expected to work as long as possible rather than taking time off. The lack of family-friendly working policies – such as shared childcare leave, flexible working hours and on-site childcare facilities – regularly makes women (typically the lower earners) choose between their career and having children. Even though Japan and Korea offer up to 52-weeks of shared paternal leave, the cultural pressure and restrictions on eligibility still limit the uptake among men to only 8.4% and 14.1%4 respectively. Countries and regions such as Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam, the Philippines, and Hong Kong still do not offer paid paternal leave for fathers.

Gender diversity on the board and our engagement

Given the economic value that a diverse workforce can bring, as a responsible investor we strive to support the elimination of the barriers that hinder gender equality, starting with Studies from McKinsey5 and the International Financial Corporation6 suggest that an inclusive and diverse workforce at the highest leadership levels can lead to outperformance over less diverse peers. Companies should therefore strive to widen the pool of potential candidates for board and management roles to ensure they draw on the richest possible combination of competencies and facilitate positive dynamics.

Approach with culture sensitivity – As an international investor we approach discussions around gender diversity with sensitivity as we are also conscious that cultural norms and nuances must also be considered. Therefore, our engagements are based on deep research into the cultural environment and regulatory landscape, aligning with local policies where relevant.

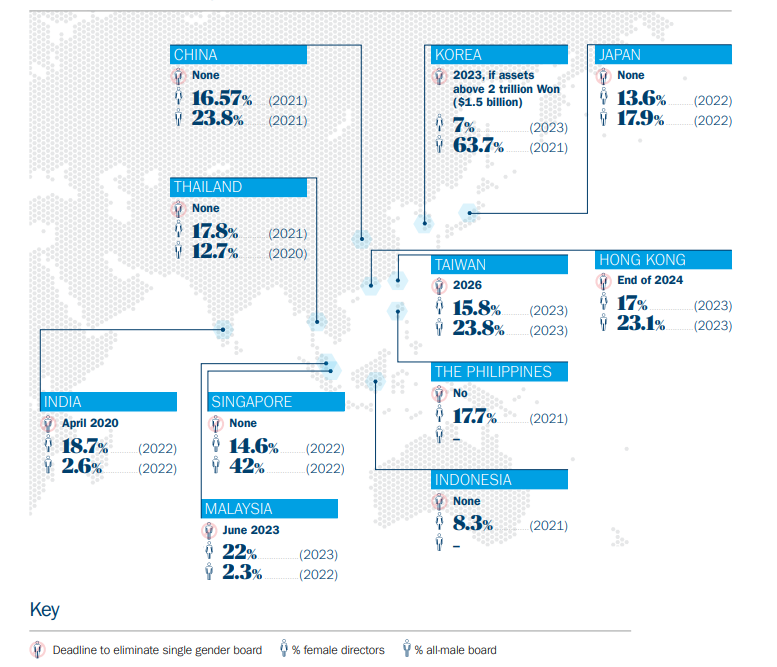

Project progress – Within our Responsible Investment team, we started the “Improving Board Gender Diversity in Asia” project in 2023, aiming to engage 26 of the most influential companies in Asia that still have all-male boards. We contacted all companies to share our aspirations around gender diversity. These are currently set at 13.5% in developing markets, and we invite companies for a dialogue to understand their plans. These discussions aid our analysis of gender diversity plans and the hurdles that they face. Where required, and in close collaboration with fundamental research analysts and portfolio managers, we also voted against directors when appropriate to escalate our concerns. We saw good progress, having engaged 26 companies in the project on this topic across 34 engagement activities. We observed 15 companies adding a female director to the board (as of 31 January 2024). We are encouraged that governments in this region are stipulating rules including the requirement for at least one female director at the board level as one of the ways to combat gender imbalance in the workforce.

However, we still see slow progress in some companies due, in large part, to the low cost of non-compliance. In India, the fine for non-compliance with gender diversity targets is capped at ₹350,000 (around $4,250) for listed companies. In South Korea, the regulator requests around 150 companies with assets above ₩2 trillion to eliminate single gender boards. They don’t, however, face any penalty or disclosure obligations for non-compliance. On the other hand, Malaysia did not impose any sanction on non-compliance companies but choose a “name and shame” approach and championed the ‘diversity chart’.

Board gender diversity – more work to be done

Source: Columbia Threadneedle Investments as at February 2024.

Conclusion

Many Asian countries are currently facing the challenges associated with balancing traditional values and modern societal roles. If not managed properly, it might have a long- term detrimental impact that could take decades to reverse. Governments and the workplace must act faster to adapt, and we believe it is also beneficial for companies to broaden the talent pools, address glass ceiling problems and facilitate a healthier work-life balance for employees. Ultimately, we expect to see progress towards these as a key part of avoiding further demographic and economic crises caused by gender imbalance and the realisation of a workforce’s full potential.

There is a long road ahead for some Asian economies if we are to normalise more gender-balanced corporate boards given that top executive women remain a rarity. Furthermore, the process by which women are added to the board must be scrutinised, as some companies might choose to appoint female relatives (wives or daughters) of the controlling shareholders to the board as a token measure. We will continue to focus on engaging with companies that still have an all-male board, encouraging them to consider a time-bound target and a robust gender diversity policy.